66 years ago

33 years ago

Now

+42°CDayNight+24°C

Let's start with the basics. What is the Hajj? Simply put, it is a sacred duty for every Muslim who can afford the journey and is healthy enough to make it. For most pilgrims, it's a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and obligation.

For Saudi authorities, it's a vast planning exercise repeated every year. Flights, visas, accommodation, transport, medical cover: every part is modelled, monitored and adjusted. And each year adds more data: satellite views of crowd density, real-time bus tracking, and even measurements of mobile network load. Look closely, and you see how faith and modern systems now work side by side.

So what happens when the Umrah runs at this scale? How do you move millions through a small set of sites without turning every entrance into a queue? How do you keep the pace steady when arrivals peak, groups overlap, and the city keeps receiving new waves every day?

The answer lies in careful planning, attention to detail, and in treating the Umrah as a year-round system designed for continuous flow. It starts before pilgrims even land. Visas need to be processed, flights and airports coordinated, transport assigned, and accommodation matched to schedules. On the ground, the job is to keep routes clear and predictable, spread out arrivals, and avoid slowdowns at key points.

Lightweight shade canopies now line key routes during the Hajj, reducing heat stress for millions of pilgrims.

In some years, the Hajj falls in the hottest weeks of the year, with temperatures in Mecca reaching 45–48 °C. This happens because the Hajj follows the Islamic lunar calendar, which is about 10–11 days shorter than the solar year. As a result, the pilgrimage dates shift earlier each year and complete a full circuit through all four seasons every 33 years. One cycle takes the Hajj into midsummer, the next pulls it back into spring or winter, and then the pattern repeats.

Lightweight shade canopies now line key routes during the Hajj, reducing heat stress for millions of pilgrims.

By 2100, parts of the Arabian Peninsula could warm by up to 9°C.

So what do you do when the weather refuses to ease up? You stop treating heat as background and start treating it as a design constraint. Routes are planned with shade in mind. Surfaces are chosen for what they do under direct sunlight. Waiting areas, tents and walkways are built around the basic question of how long people will be exposed and how much relief you can provide along the way.

By 2100, parts of the Arabian Peninsula could warm by up to 9°C.

That is the logic behind the cooling measures now spread across the sites. They're not add-ons or nice-to-haves. They are part of how the Hajj is engineered: small interventions, repeated at scale, to make the environment more manageable for millions of people moving through it.

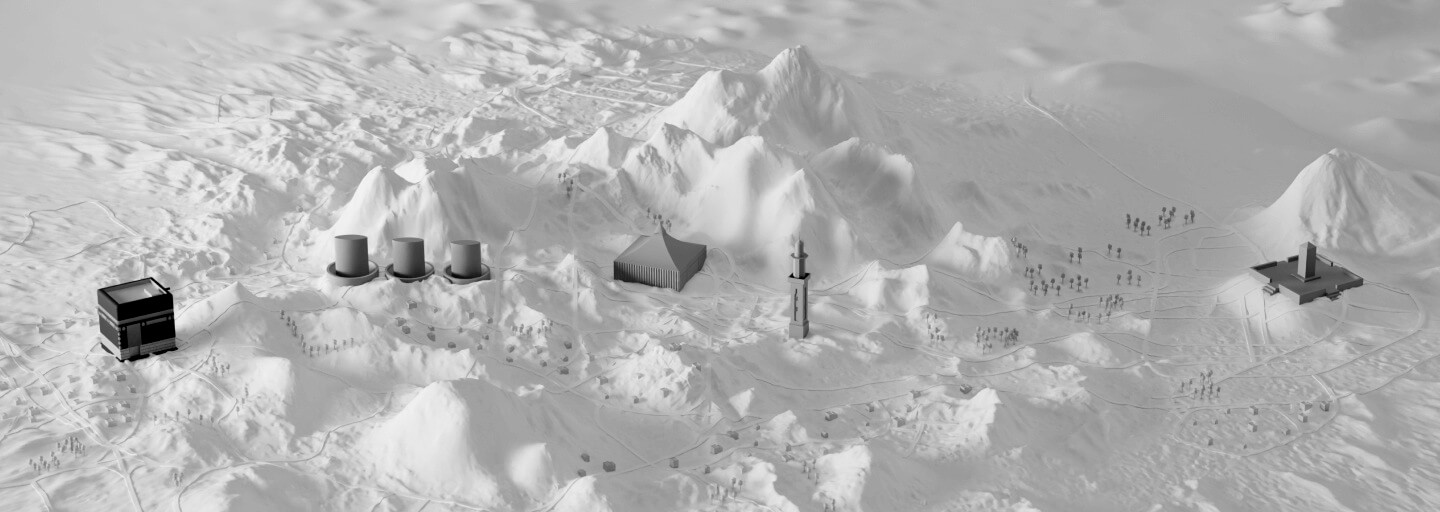

We'll continue exploring the Hajj journey in our next instalment, where we'll walk through 3D models of the pilgrimage sites and explain the rituals behind them.

Centuries ago, pilgrims crossed deserts in slow caravans. Today, millions move through Mecca as if part of a single organism. The Hajj and Umrah are still spiritual journeys, but they also operate as vast modern systems, with digital corridors and careful engineering of time and space.

The numbers still tell a remarkable story. Look closely at the flow, the precise timing, and the choreography of people. Behind what seems like an ancient ritual is a living pattern of humanity learning how to move together.

We'll continue exploring the Hajj journey in our next instalment, where we'll walk through 3D models of the pilgrimage sites and explain the rituals behind them.